Scale or Die – The Curious Case of Nigerian Founders

When we started Sidebrief, we had a simple thesis: to capture Africa’s 1 billion+ population opportunity, businesses need to scale beyond their primary markets. So, build the platform to help businesses grow and scale across Africa like it’s a single market.

Boy, were we wrong. Not about the opportunity – that’s very real – but about the fundamental nature of what we were solving. This isn’t a story about scale. It’s about survival. For many African founders, expansion isn’t just about capturing more value – it’s about staying alive. The market risks in building a business in many African countries are immensely diverse and sometimes so profound that building across multiple markets is not just a growth strategy – it’s the survival kit.

Nothing exemplifies this in recent months better than the massive currency devaluation that Nigerian founders have had to deal with. While the reports of many public companies showed the bloodshed that it has been, not many startups and small businesses have talked about it in numbers. So, one day, over late night finger biting and gnashing of teeth as we reviewed our YTD numbers from Nigeria, we decided we should talk about it, because not only have we seen it ourselves but worked with hundreds of other businesses going through it.

Now then, let’s walk through the impact of devaluation on three critical impact areas for startups and small business, and how exposure to another market just might be the elixir of life: revenue, costs, and talent.

Revenue

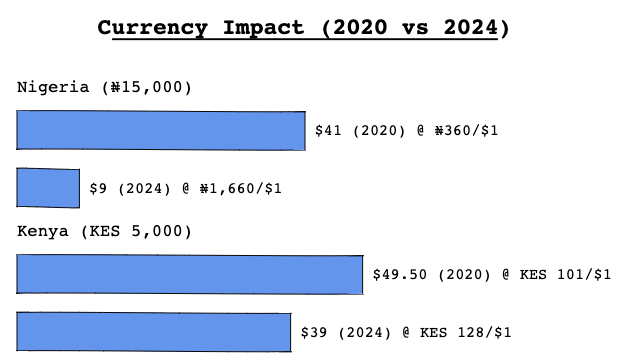

In 2020, our lowest tier pricing in Nigeria was ₦15,000 ($41). In Kenya, a comparable pricing was KES 5,000 ($49.50). Fast forward to 2024, after a brutal 360% currency devaluation in Nigeria over 4 years, the same ₦15,000 service is worth $9, while the Kenyan service holds at $39.

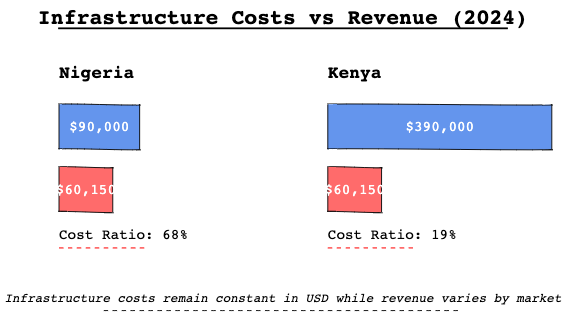

For 10,000 users, your Nigerian revenue has gone from $410,000 to $90,000 because the Nigerian Naira has spiralled downwards in multiple fits of monetary policy summersaults. So to match your 2020 numbers in USD terms, you’d need to quadruple your user base and then do maybe 4x more to deliver growth, while hoping that the currency stays sane (yes, it won’t). Meanwhile, your Kenyan operation, while not immune to market pressures, has maintained relative stability, moving from $490,500 to $390,000, not ideal but you will take it.

If you are wondering why report in dollars as a Nigerian business earning in Naira and serving Nigerian users; your competitiveness to investors is measured in USD, your infrastructure costs are in USD, and your talent thinks of compensation in USD. You have often heard the argument that startups should raise in Naira from local investors yada yada yada. Remember to also build your data centers, tools etc, and only hire Olakunle who has no ambition to earn like his global contemporaries. Also, build your path to follow-on funding and exit in Naira, you will need it.

Costs

It gets more painful. When your currency takes a beating, your infra stack doesn’t send sympathy cards. Your AWS bill stays stubbornly in dollars, and EC2 instances don’t care about naira devaluation. Your $2000 monthly server costs are now eating ₦3.4 million instead of ₦800,000. GitHub doesn’t offer a “sorry about your currency” discount – that Enterprise plan now costs your Nigerian developers ₦35,700 instead of ₦8,400. MongoDB Atlas isn’t adjusting their pricing tiers for African markets – your $199 dedicated cluster now demands ₦338,300 versus yesteryear’s ₦79,600.

Stripe doesn’t customize their per transaction fees for struggling economies. G Suite, Linear, Slack, Notion, SendGrid – and the entire backbone of modern SaaS infrastructure – they all bill in USD and couldn’t care less that your naira is worth less. Even basic development tools like JetBrains IDEs or Postman’s team plans become luxury items when your local currency tanks as a startup or small business.

Global standards peg infrastructure costs at 20-30% of revenue, we’ll use an optimistic 15% for Africa (and yes, if you’re hitting these numbers, you should be teaching Masterclasses). Here’s the kicker, in Nigeria, your infra costs will stay at $60,150 to serve your 10,000 users, while your revenue nosedives from $410,000 to $90,000. That’s gone from a healthy 15% cost ratio to an impossible 68%. Your Kenyan operation? Still maintaining a manageable 19% cost ratio.

The Price Raise

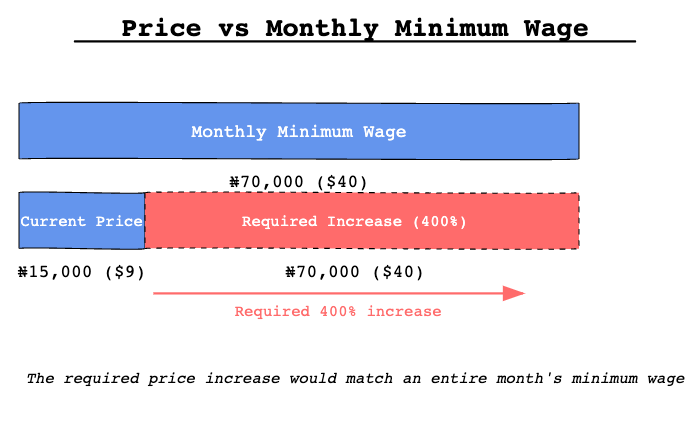

So, how about we just raise prices in Nigeria then. To get back to that magical $40 price point from 2020, we’d need to raise our Nigerian prices by around 400%.

Except – let me paint you a picture of what “just raise prices” means in context:

- The monthly minimum wage is ₦70,000 ($40). Not hourly. Monthly. We’d be asking for a month’s minimum wage. Even a $10 increase takes you to $19, which is half the minimum wage.

- The World Bank delicately calls Nigeria “the poverty capital of the world” and inflation is running at 34%. This isn’t just a statistic – your users are literally choosing between food and transportation. Go on then mate, quadruple your prices.

In a market where your target market is simultaneously dealing with currency collapse, runaway inflation, and purchasing power cannot afford anything not in a sachet, your price increase better come with a side of miracle to justify it.

Talent

But with $40 as minimum wage, talent is cheaper right? Here’s how that plays out (numbers are real):

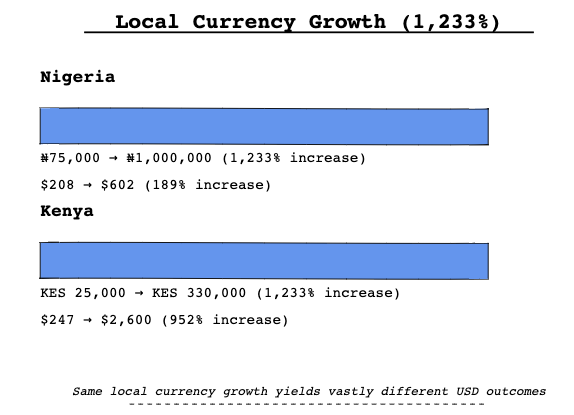

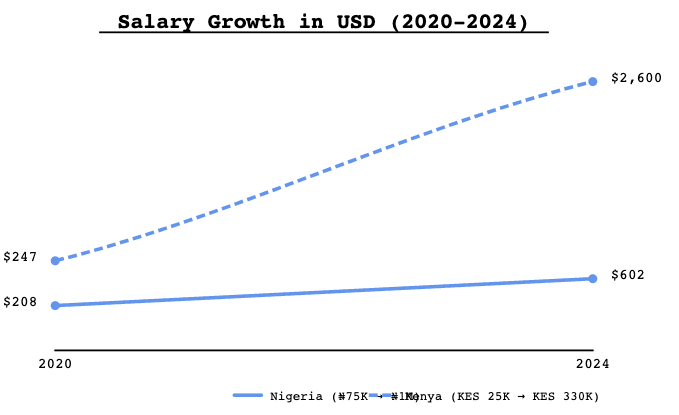

A Nigerian employee in 2020 earns ₦75,000/month ($208 at ₦360/$1) as entry level. By 2024, through promotions and raises, their monthly comps has grown to ₦1,000,000 – that’s a 1,233% increase in local currency terms! On paper, this looks like extraordinary growth. Let’s apply the same growth rate to a Kenyan employee starting at KES 25,000 ($247 at KES 101/$1). With a 1,233% increase, they’d now be earning KES 330,000.

The Nigerian employee, despite a massive 1,233% raise in naira terms (₦75K to ₦1M), only sees their actual purchasing power increase from $208 to $602 (at ₦1,660/$1) – that’s a 189% increase in USD terms. The Kenyan employee, with the exact same percentage increase in local currency (KES 25K to KES 330K), sees their USD value income go from $247 to $2,600 (at KES 128/$1) – that actually means something when everyone is jostling for top talents.

So yes, it’s cheaper to hire ‘labour’ in Nigeria, but world class talent will want comps similar to global standards, or at least something better than working in a denim sweatshop. Turns out you have a better chance of retaining your Kenyan talent than the Nigerian counterpart, not because you won’t try to, but because naira will try harder than you to dispose them.

This is why retaining top talent in Nigeria has been near impossible these past years. The best comps for your talents in naira terms gets demolished by currency devaluation. When your Nigerian Head of Marketing can make 10x their income by working minimum wage shifts in Co-op South Croydon while undertaking Masters in African Studies and Culture, writing visa support letters better be a company employee incentive you offer.

This is the reality. It’s tough.

Multi-market presence isn’t just a growth imperative; it’s your best shot at staying in the game. The concept of “the African market” is a maze of 54 distinct economies, each with its own rules, risks, and bizarre twists. Building across multiple markets isn’t just smart strategy – it’s your best hedge against market risks.